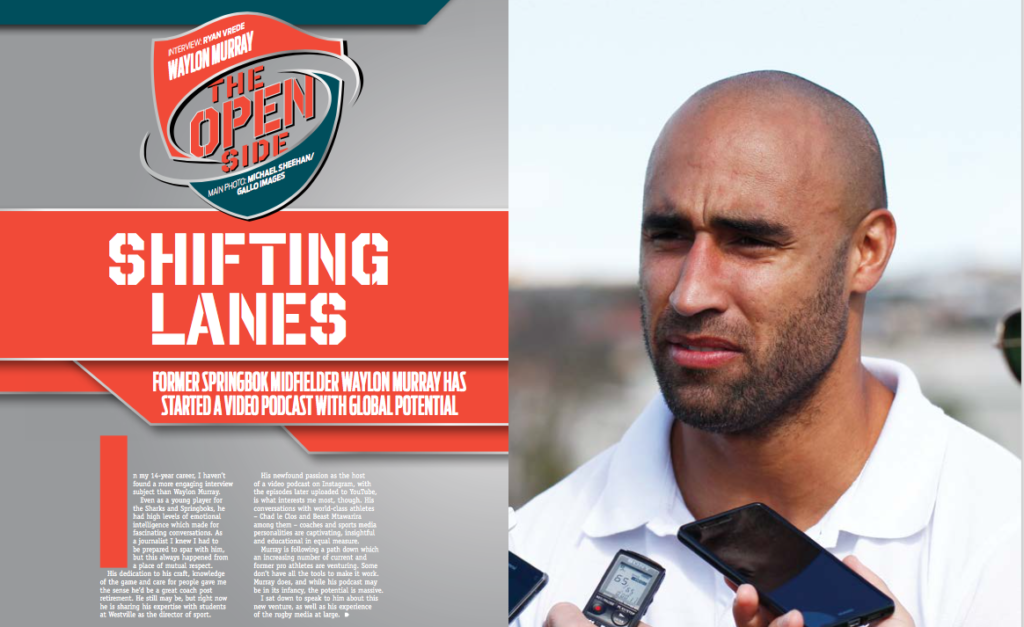

Former Springbok midfielder Waylon Murray has started a video podcast with global potential, writes RYAN VREDE in the latest SA Rugby magazine.

READ: What’s in our latest issue?

In my 14-year career, I haven’t found a more engaging interview subject than Waylon Murray.

Even as a young player for the Sharks and Springboks, he had high levels of emotional intelligence which made for fascinating conversations. As a journalist I knew I had to be prepared to spar with him, but this always happened from a place of mutual respect and trust.

His dedication to his craft, knowledge of the game and care for people gave me the sense he’d be a great coach post retirement. He still may be, but at this point he is sharing his expertise with students at Westville as the director of sport.

His new-found passion as the host of a video podcast on Instagram (episodes later uploaded to YouTube) is what interests me most though. His conversations with world-class athletes – Chad le Clos and Beast Mtawarira among them – coaches and sports media personalities are captivating, insightful and educational in equal measure.

Murray is following a path down which an increasing number of current and former pro athletes are venturing. Some don’t have all the tools to make it work. Murray does, and while his podcast may be in its infancy, the potential is massive.

I sat down to speak to him about this new venture, as well as his experience of the rugby media at large.

Before we jump into what you’re doing with video podcasts, let’s chat about your relationship with the media during your career …

As a young player I read all the articles to see what the media thought of me. If something bad was written, it would be tense when I saw the writer again. It would definitely affect me. Then one day [former Sharks loose forward] Warren Brits told me to stop reading those pieces because whether there was glowing praise or harsh criticism, it didn’t matter. As players we know when we’ve played well or poorly. We don’t need anyone to tell us. So I stopped doing that and as I became more emotionally mature I developed more understanding of the journalism profession and respect for journalists.

What was your experience like when it came to the level of professionalism journalists exhibited?

We’ve spoken before about how important it is for pro athletes, who sacrifice a chunk of their lives to their craft, to be met with the same level of professionalism from the media. For most of my career there was a mismatch in this context. This created an uneasiness because players weren’t always certain their words would translate in the ways they intended. When there is professionalism, integrity and trust, that makes things a lot better. That isn’t to say there aren’t journalists who embody that; there certainly are. And you’ll find those guys are highly respected among the players.

What do players wish journalists asked them more and which topics do they prefer to avoid?

I understand the importance of analysing a performance and the technical side of the game, but I wish they’d ask more questions that revealed players’ humanity. That will give people more insight into who the players really are, as opposed to focusing on aspects of what they do. I would have loved to speak about mental health and general well-being, or what types of leadership styles resonated with me, those sorts of topics.

When you look at sport as a product in the US, and how the sports media operate, how do you feel about our landscape?

It’s a great package. Most players aren’t afraid to speak their minds because they trust journalists to convey the message they intend, and if that doesn’t happen, there are serious consequences for those journalists. Sports media personalities aren’t afraid to ask the hard questions and are usually incredibly well prepared and knowledgable to go with decades of experience in professional sport, which gives weight to their opinions. This makes for a great viewing experience. In SA, players are pretty conservative. There are numerous reasons for this, one of those being trust issues I mentioned earlier. But during the pandemic you started to see more find their voice, which is great and should continue.

How important is it that journalists have a deep understanding about the all aspects of the game, especially the technical dimensions?

Very important. If a journalist is critical of you for whatever reason, it’s easier to take if their opinion is underpinned by a deep understanding of the game. You don’t have to agree with them, but at least you can see their point of view and, for the players who are emotionally mature enough, engage them in a productive debate without letting your emotion cloud the conversation. The best media personalities in the US bear witness to this. They come in with a deep understanding of the game, know the history of the topic they’re discussing, are aware of the trends and therefore speak from a position of power.

What about the old line peddled by many players, that if you haven’t played the game at a pro level your views on it are illegitimate?

That is such nonsense. Absolutely bogus. Of course there are players who think like this, but there is no basis for it. If I don’t like journalist X, I have to have legitimate reasons for that, and one of those can’t be that he or she wasn’t a professional athlete because that assumes they haven’t invested years and years in mastering their craft. I also think that the system is weighted in favour of the players. Journalists spend years on the sidelines at training and at matches, all the domain of the players and coaches. But I’ve never heard of a player spending a day with a journalist, trying to understand the forces that shape their world. The cross-pollination of ideas is important. It’s something I try to implement in my role as director of sport at Westville. Coaches from across our different codes sit together and discuss their plans, structures and culture in a bid to make the collective stronger. This has to be the relationship between professional athletes and the media. Players gain nothing from staying in their protective bubble.

What sparked the idea for the video podcast?

It started out as a way to keep our students and sportspeople engaged and stimulated during lockdown. I figured that I could use my network in the game to add value to their lives through conversations with sports personalities, which includes players, coaches and media. I really just want to be of service to our students, but it seems to have grown beyond that and appealed to a broad audience, which is great. I’m able to help reveal the humanity in these sports personalities, which is important to me. Most people can’t relate to athletic feats because they aren’t gifted in that way, but they can relate to things these personalities have been through in their lives, and perhaps take the learnings from that and apply it in their lives.

Players taking control of the stories is a trend that’s grown exponentially over the last five years or so. Did this always interest you?

I’ve always been drawn to connect on a human level. Rugby is what I did professionally but it isn’t who I am. When I sat in change rooms, we rarely spoke about sport, the conversations were mostly about life. So I started the video podcast with the intention of connecting with people on a human level. Again, the main catalyst for this was to be of service to the students at my school. I’ve always been more interested in growing good humans who contribute significantly to society than I have been in developing superstar athletes. That would be a great outcome, but it has to be a byproduct of building great men. It’s a leadership style that worked for me. Brad Mooar, the newly appointed All Blacks assistant coach, led like this and I saw the fruits of it. It isn’t a coincidence that the Crusaders won three Super rugby titles on the bounce after he joined the coaching team. He obviously has immense technical knowledge, but his EQ is equal to that and makes him the coach he is.

Speaking of EQ, rugby was home to a pretty toxic brand of masculinity, but recently we’re starting to see the stigma associated with mental health disappear. That must please you?

It does, because during my career I needed that aspect of leadership to come through more strongly. But the culture was different then. You only knew what you knew, so I don’t blame anyone. Now players are far more comfortable speaking about mental health issues, which is great because all of them are confronted with it in some form or another. There are many more coaches who prioritise this as well, guys like Sean Everitt at the Sharks. A coach with high EQ levels is critical to making the collective work. We saw this in the Netflix documentary The Last Dance where Bulls coach Phil Jackson was able to make a team of so many different personalities into a highly efficient and champion unit.

What’s your vision with this video podcast?

I don’t have a lot of expectation beyond what it is now. I can see the potential for growth, but that needs to happen organically, I’m not going to force it. If it stays what it is now – a platform to reveal the humans behind the athletes – then I’d be content. If it scales up, I’ll just go with it.