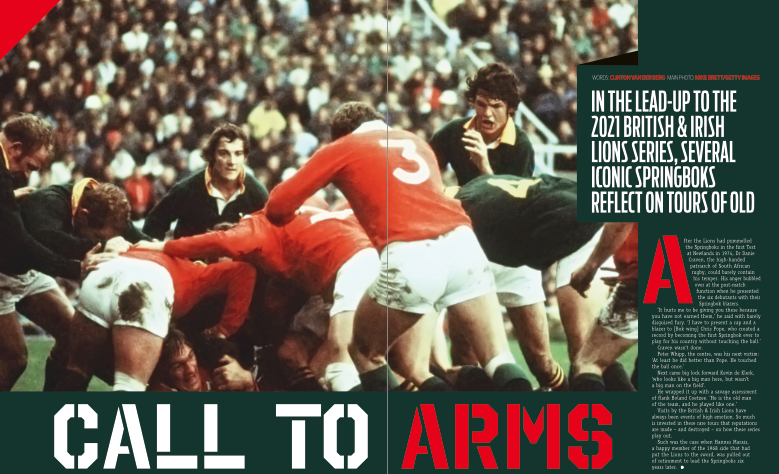

Ahead of the 2021 British & Irish Lions series, several iconic Springboks reflect on tours of old.

After the Lions had pummelled the Springboks in the first Test at Newlands in 1974, Dr Danie Craven, the high-handed patriarch of South African rugby, could barely contain his temper.

His anger bubbled over at the post-match function when he presented the six debutants with their Springbok blazers.

‘It hurts me to be giving you these because you have not earned them,’ he said with barely disguised fury. ‘I have to present a cap and a blazer to [Bok wing] Chris Pope, who created a record by becoming the first Springbok ever to play for his country without touching the ball.’

Craven wasn’t done.

Peter Whipp, the centre, was his next victim: ‘At least he did better than Pope. He touched the ball once.’

Next came big lock forward Kevin de Klerk, ‘who looks like a big man here, but wasn’t a big man on the field’.

He wrapped it up with a savage assessment of flanker Boland Coetzee. ‘He is the old man of the team, and he played like one.’

Visits by the British & Irish Lions have always been events of high emotion. So much is invested in these rare tours that reputations are made – and destroyed – on how these series play out.

Such was the case when Hannes Marais, a happy member of the 1968 side that had put the Lions to the sword, was pulled out of retirement to lead the Springboks six years later.

‘We thought the Lions would be just another bunch of typical Engelse [English] who tried their best but would be too soft and would crack under the physical pressure of a tour to South Africa. That happened in 1968, and we thought it would happen again,’ said Marais, now aged 79.

The tour of ’74 rates among the most famous in history for a myriad reasons, not least the mythology that sprang up and continues, even now.

One of these surrounded the ‘99’ call, a call to arms devised by the Lions of one-in, all-in: if one copped a punch, they would all react.

Violence predictably erupted in the third Test, dubbed ‘The Battle of Boet Erasmus’.

‘I was not aware of any special 99 call. When the Lions started punching, I just assumed one of our guys had done something stupid to make them so angry,’ said Marais.

‘The 99 call is a good story and it has been told again and again, but it soon became clear that the Lions had decided they would not come second in the physical exchanges. The first time I scrummed down against Ian McLauchlan, he took me roof high. He clearly meant business.’

On that same tour, the Springboks trained at Baviaanspoort Correctional Services ahead of the second Test in Pretoria; a shrewd move that guaranteed no journalists were allowed in.

The jokes practically told themselves. One story claimed that Dimitri Tsafendas, imprisoned for assassinating Hendrik Verwoerd, the prime minister, six years before, had served the Boks tea and biscuits after practice.

If the humour was dark, so was the mood.

In Luke Alfred’s book When the Lions Came to Town, Morne du Plessis tells of sitting in the Springbok bus at Loftus Versfeld before the second Test and noticing that the Lions were singing while the Bok bus was tjoepstil.

‘Our bus was a funeral procession. You wouldn’t have dared crack a smile. They were happy and singing and I thought to myself, “There has to be more to rugby than this.”’

If they were grumpy then, who knows how they felt after the 28-9 belting.

The mood was bleak and continued through the tour, which concluded at Ellis Park. There was no respite. Naartjie sellers were banned and fans had to live with the cold reality of having no ammunition.

Six years later, the Boks were in better fettle when Bill Beaumont’s Lions arrived.

‘It was massive,’ recalled Ray Mordt, the powerful wing who played in all four Tests.

‘It was still the days of apartheid and the game was white and Afrikaans. Rugby was everything to the Afrikaners,’ said the Rhodesian-born powerhouse, who couldn’t speak the language.

‘We lost terribly in ’74 and I remember listening on the radio – we had no TV in Rhodesia. Six years later, there I was. It was a dream story, something huge. It was the second-biggest game you could have, after the All Blacks.’

He said the Boks were on to something good: Morne du Plessis was an ‘incredible’ captain; the Naas Botha era was starting and Gysie Pienaar was in his pomp.

The Boks won the series 3-1, which went a long way to redeeming themselves after the horrors of ’74.

Mordt says that the frequency of All Black Tests now makes matches against the British and Irish Lions the biggest of all, because they are so infrequent.

‘Our players might be a little underdone, but South Africa is the toughest place to come and play. We must make sure of that. I’m glad Rassie Erasmus is in charge with Jacques Nienaber, both astute men. I hope we don’t run out of time, to get conditioned and to get sharp.’

Rob Louw, the tearaway flanker, was among the heroes of the 1980 series.

He picked up tries in the first two Tests – despite being deathly sick in the week leading up to the second one, in Bloemfontein — and thrived with the Boks’ switch to a counter-attacking game.

Six years previously, he had attended the first Test in Cape Town and then drove with his dad to Port Elizabeth for the third, memorable for its violence.

‘The Lions gave us a proper hiding,’ he recalled. ‘It was my absolute dream to play against them.’

Six years later, he got his chance.

‘Our forwards got klapped. But we beat them through counter-attack, scoring five tries at Newlands at the start. Nelie Smith was a really good coach. Now, New Zealand and the Crusaders play like that.’

It suited Louw, whose game was wide and roving and easy on the eye.

When the Lions mauled, he would jump out and help Botha, proving an extra man in the backline defence. The Bok backline, recalls the two-time SA Player of the Year, was a thing of beauty with Pienaar especially lethal. He cut the Lions to pieces.

Add in the like of Mordt, Willie du Plessis, Gerrie Germishuys and Botha, and the Boks had the backline to compensate for any failings up front.

Louw is a big fan of northern hemisphere rugby, noting how strong the club scene is – pockmarked with top SA player performances – and how energised the Six Nations was.

‘We are lucky having such a big, physical advantage [over most]. But the Lions will be tough, especially as our guys haven’t played. Thank goodness for Rassie and Nienaber. They’ll make a plan.’

After 1980, it would be another 17 years before the Lions returned. When they did, they upset the Boks in the first match at a damp and miserable Newlands, winning 25-16.

‘The result absolutely shocked me, maybe because I had never considered it possible,’ Gary Teichmann, the captain, wrote in his book For the Record. ‘It felt far worse than defeats against the All Blacks or Wallabies. I could see our guys were genuinely stunned, left almost speechless.’

Things were to get worse at his home ground in Durban, where Jeremy Guscott’s wonder dropped goal proved pivotal and secured the series.

‘At the final whistle, I felt instantly drained. I found it so hard to accept we had lost the match that we had so comprehensively dominated. A stone-silent Springbok changing room had become a familiar experience for all of us.’

Yet there were great days to match the bad. As was the case in Durban for the first Test of the 2009 series, memorable in the main for Beast Mtawarira’s super-human scrummaging performance against Phil Vickery.

‘I haven’t seen a side get scrummed like that for ages,’ said John Smit. ‘In the old days you saw it often because there were no rules, but it will be a long time before you see a Test prop get a hiding like the one Vickery got from Beast.

‘When Beastie is “on”, he’s “on” and nothing can stand in his way, and he was “on” that day. I could see the shock in the Lions’ eyes. They couldn’t believe what was happening to them as they got shoved about or gave away penalties. They couldn’t do anything.’

Johann Rupert, the SA business magnate, had handed out the Springbok jerseys, telling the players, ‘Guys I have been fortunate to have made all the money that I could possibly need, but with all that money I still can’t buy one of these.’

The moment had a sweet irony: the year before, coach Peter de Villiers had accused Rupert of being a ‘third force’ out to get rid of him.