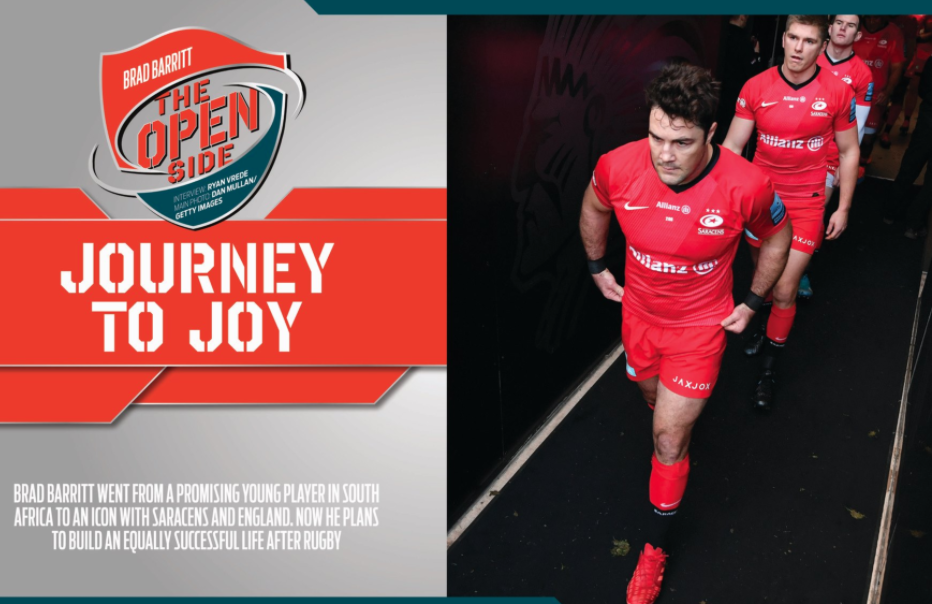

Brad Barritt went from a promising young player in South Africa to an icon with Saracens and England. Now he plans to build an equally successful life after rugby.

READ: What’s in our latest issue?

I want to start with your decision to leave for England over a decade ago. There’s an assumption that every elite South African player wants to play for the Springboks. I’d suggest in the absence of a clear pathway to that goal, every elite player wants to play at the highest level, even if it isn’t for the country of their birth. Was that the case with you?

Mine was slightly more complex, because I have a strong English heritage. My mom is English and I may have been the only kid in Durban being immersed in the importance of Yorkshire pudding [laughs]. My dad is Zimbabwean and my parents only moved to Durban a couple of months before I was born. So while I took great pride in representing the Junior and Emerging Boks and I supported the Springboks by virtue of the fact that I was born in South Africa, I always had an affinity for England. Theirs was the first rugby shirt I wanted as a kid, and when the opportunity came to join Saracens, it seemed like a stepping stone towards the goal of playing Test rugby for England. I’ll forever be grateful for my experience at the Sharks. We built something really special and it remains one of my great memories, but my career took a different path.

How would you describe the fear of leaving for the unknown?

I was quite young so I saw it as an adventure. I wasn’t really burdened by fear at all. It made sense to me on a number of different fronts. I knew that if rugby didn’t work out, the educational opportunities I was exploring would form the basis of a life in England. I followed my heart and I didn’t allow myself to question the decision once I made it. I just committed and dived in. I made the right call. I can’t offer anyone else advice on this because everyone’s circumstances are different. But as a guiding principle, once you make a big life decision, you need to fully commit to it.

Once there, I’d imagine the real challenge was establishing yourself as a Saracens player?

I came in a bit torn. On one hand I was nervous and wanted to prove my worth quickly, and on the other I was confident that I would not only make it as a pro at the club, but have a long and successful career. Also, the culture when I arrived and what it would become five years later were night and day. We had good players, but we were chronic underperformers and that had a lot to do with the culture at the club. In honesty, the first six months were incredibly destabilising because of this. We had no identity and in that period 22 players left the club. It was challenging but we eventually laid the foundations of what became an excellent culture aimed at consistently high performance.

You’ve had a titanium plate inserted into your cheekbone, a metal plate inserted under eye socket, and lacerated an eyeball on a tour to SA. What did serious injuries teach you about yourself?

Early in my career I had an air of invincibility but serious injuries humble you and drive home just how fragile a career in professional sport can be. Thankfully, medical science has developed to the point where it’s rare that an injury ends your career. So at no stage did I think I wouldn’t come back. The rehabilitation process is the hardest and it exposes your mental resilience. If you let it, it will grow that resilience and make you a better man, not just player.

Why do you think you had a longer and more successful career than some players many would consider more talented?

I’ll answer this question by stripping it back further. I truly believe that a player’s experience in his formative years at school lays the foundation for the professional he becomes. That’s why I’m in favour of weight-based rugby at school level. I’ve seen so many guys who mature physically or mentally quicker at school, absolutely dominate the opposition throughout their schoolboy careers. However, when you get to the pro ranks, there is very little to choose between the players physically, and because those kids are used to running over, around and through defenders, they don’t have the tools to adapt and find solutions when that doesn’t happen. Temperament comes from years of having to find a way of overcoming challenges, and if that doesn’t happen in your formative years, your talent isn’t enough as a pro.

Let’s talk about composing a champion team. As a Liverpool supporter I never understood why we persisted with Jordan Henderson. He was clearly less gifted in the primary ways that people judge elite footballers. But in time I came to understand his immense value in the context of the collective. Without him, they are not a champion team. I see you in quite the same way. Is that how you see yourself?

I’d like to be remembered as a player that allowed others to shine and who quite enjoyed the game’s less glamorous dimensions. Ultimately people will always try to find flaws in your game, but I’ve always been more interested in what players do well and how to maximise those strengths.

How has coaching changed since the start of your career?

Dramatically, because the game looks completely different to what it did 15 or 20 years ago. The game has gone through so many law changes, and the best coaches are the ones who’ve been able to adapt and manipulate the laws in their team’s favour.

What about leadership?

There is definitely a massive difference. When I started at the Sharks we had a strong core of senior players and the culture was that young players’ needs and thoughts weren’t really that important. I can’t speak for other teams, but at Saracens I tried to lead collaboratively, understanding that there are players who definitely know more than me and are able to fill those gaps in my knowledge, if I let them. My philosophy is that to be most effective you need to be the most credible, and you gain that credibility by not hiding behind the facade of being all-knowing. When people are empowered and given a sense of ownership, your job becomes a lot easier.

While I know being in a committed relationship isn’t for everyone and a player’s support network doesn’t have to include a committed partner, but let’s discuss the importance of choosing the right partner for an elite athlete. Why it is so important in real-world terms?

Because what people perceive to be our lives is actually just a small percentage of our lives. For the bulk of it, it is the mental and physical strain you endure. And the longer you play, the more the effects of that become extremely dangerous if you don’t have effective coping strategies and a strong support network. I’ll give you an example of how Georgia has made a massive difference for me. In 2013 I endured a period where we were knocked out of the Champions Cup and lost the Premier League in consecutive weekends. A day after the latter, I had to get on to a plane to New Zealand with players from [the champion] Northampton Saints as part of the England team. I couldn’t bear the thought of that and I was on the verge of pulling out. I was devastated. But Georgia helped me overcome that. In hindsight, pulling out of the squad would have fundamentally shaped my life, but her intervention changed everything. There are so many experiences that can break you as a pro athlete, so the value of a strong support system is immeasurable.

Let’s finish with your entrepreneurial spirit. How was that forged and developed?

It dates back to high school, where it was drummed into me to cultivate a pathway to professional independence. Education was key to that, and it’s why I did my masters in business science while playing. I’ve always told myself that I’m going to be more successful post-rugby than I was during my career, and that’s still the focus. I’d attend evening lectures at the University of Hertfordshire after training. That was hard and I nearly gave up a couple of times. But I always knew there was a bigger picture. I’m involved in a couple of different businesses but the most recent, Tiki Tonga Coffee, is really starting to take off. It’s the official coffee of Tottenham Hotspur and we’ve done collaborations with some big brands, including Guinness and Nike. I was fortunate that the culture at Saracens encouraged players to explore their interests outside of rugby. As a leadership group, we said that we need 20% of their time and during that time, we demanded 100% of their effort. What they did with the other 80% of their time was their business, but we encouraged players to invest in themselves in which ever ways were beneficial to their growth as people. The notion that players need to be completely consumed by the game is nonsense. It is what we do, not who we are.