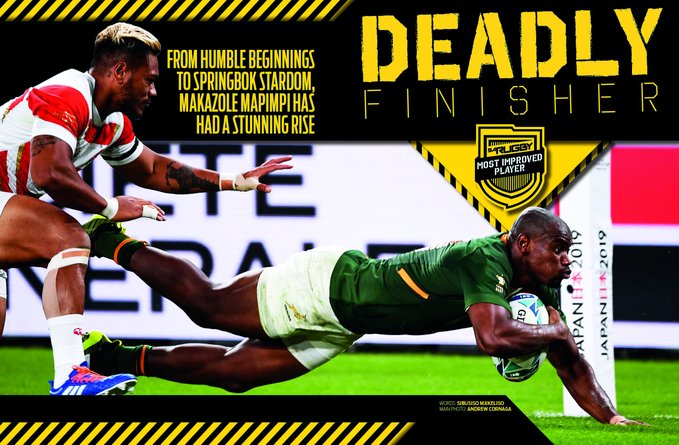

From humble beginnings to Springbok stardom, Makazole Mapimpi has had a stunning rise, writes SIBUSISO MJIKELISO.

Makazole: the name means he who must be calm and show humility. Mapimpi: he of cobras. Springbok World Cup-winning wing Makazole Mapimpi had lived this paradoxical existence all his life. Off the rugby field, he embodies his first name. On it, he completely belies his calmness and restraint to assume the deadly traits of a cobra.

In the year when he joined and surpassed World Cup-winning luminaries Chester Williams, Bryan Habana, JP Pietersen and other Springbok high flyers, Mapimpi showed that he is quick, combative, opportunistic and dangerous. He stands among greats of the game, holding the title of being the first South African to score a try in a World Cup final (in three visits).

He is a player that has had nothing handed to him on a plate and he did it all by being one of the most diligent workers in the Springbok squad that made history in Japan.

‘His communication and organisational skills from the wing have changed immensely,’ says Springbok performance analyst Lindsay Weyer. ‘He has grown into a complete package, where he is so reliable. The other players will always back him and say that they hear him and he’s always in their ear throughout the game.

‘In our defence pattern, that’s vital. He can score tries. We all know he is a finisher. But when it came to high balls, there weren’t too many contestable kicks he’s fielded at the Sharks or even at Border or the Kings, and at the Boks that became a priority.

‘Every training session Mzwandile Stick or myself were just kicking balls at him so he could keep improving. He’s a guy who, regardless of his age, wanted to improve himself and to learn.’

What you gather from Weyer, who knows Mapimpi from as far back as the Border Bulldogs days, through to the Southern Kings, where they worked under former coach Deon Davids, was that the Mapimpi who enters the dressing room is often markedly different from the one who leaves it.

By that account, the Mapimpi who made his Bok debut against Wales in Washington, and scored, was different to the one who scored the try that hit England like a Deontay Wilder straight right hand in Yokohama on 2 November.

‘At the Kings in 2017, I said to Deon, let’s give this bloke a chance here,’ Weyer says. ‘At the time he could hardly speak a word of English. He wouldn’t talk in a meeting or anything like that. Now he is communicating in meetings and everyone turns around and listens to him.

‘He has a presence about himself now. It’s amazing how he has evolved in that aspect. The coaches didn’t always want to explain and tell players things. The guys needed to take ownership and that’s where Mapimpi came into play and took ownership of the game play.’

Weyer is not the only one to notice Mapimpi’s growth. Lungelo Payi, the former Bulldogs second rower, served as a mentor to East London-based players after his retirement. He was particularly impressed by the work ethic the 29-year-old showed in the lead-up to, and during, the victorious World Cup campaign.

‘His game surprised me quite a bit,’ says Payi. ‘I’d always looked at some of the flaws of his game and noted that he struggled under the high ball. His defence was also not where it should have been.

‘But you could see from the pre-tournament warm-up match before the World Cup that he had worked hard on his game. Top players, if they make a mistake, are quick to tune back into the game and they never lose focus. Mapimpi was exactly like that this year. He’s not the type to feel down after an error; he is quick to dust himself off and pick himself up.’

Indeed, Mapimpi could not have ordered better aperitifs to the big showpiece than the hat-trick of tries he scored against hosts Japan in a World Cup warm-up on 6 September at the Kumagaya Rugby Stadium, where the Boks strolled over the line with a comfortable 41-7 victory.

However, Mapimpi may have been a little bit of an afterthought when Rassie Erasmus’ ‘Mission Impossible’ was being formulated 18 months ago. The real spoils were reserved for the young dynamic wing duo of Aphiwe Dyantyi and Sbu Nkosi, who lit up the inbound England series.

Perhaps ironically, Mapimpi had his best attacking year (27 tries in a calendar year in three major competitions for three unions) in 2017, when Dyantyi and Nkosi weren’t near prominence.

But then coach Allister Coetzee did not see the pressing need to include him in the national team, opting instead for Courtnall Skosan and Raymond Rhule. Dyantyi was always Erasmus’ star man on the left wing. The Lions flyer, who bombed out of World Cup reckoning through injury, followed by a positive drug test finding, had started 13 of the Bok Tests in 2018.

Mapimpi, meanwhile, spent most of that year trying to get out of Dyantyi’s shadows and getting to grips with the Sharks system, which was so dismally direct it didn’t yield too many opportunities for wing players.

But, as it turned out, Dyantyi’s 2019 misfortunes turned into Mapimpi’s ticket to Japan. ‘We knew we probably had the best four wings in the world: Aphiwe, Mapimpi, Sbu Nkosi and Cheslin Kolbe,’ says Weyer.

‘Our plan the whole time was to have all four and we were lucky Cheslin could cover fullback. Obviously, Aphiwe was probably first choice but during the Super Rugby competition, it was such a tight contest, because of the World Cup year.

‘Mapimpi was showing something that said you have to have him in the team. Aphiwe was also making good reads on defence and was a great attacking player and had shown great growth.

‘It’s just unfortunate how life works out. Mapimpi stepped up and grew into something special. I reckon, come the World Cup, with and available fit Aphiwe, it would have still been a close call for the coach on whom to pick at left wing.’

What’s incredible is that Mapimpi closed 2019 with 14 scores for the Boks in 14 Tests. For a boy from Tsholomnqa, a village outside East London, who cut his teeth playing in tournaments such as the Dali Mpofu Easter Rugby Tournament, it is a mind-blowing achievement.

Payi, now an aspirant development coach, was impressed by Mapimpi’s ability to soak up information as he rose through the ranks.

‘I don’t even think he is playing his natural position but he has adjusted very well and made it his own,’ Payi said.

‘He’s a No 14 and not a No 11 in my book. That said, he has excelled. He is helped by the fact that he is quite disciplined and doesn’t indulge in too many off-field temptations.’

Weyer sums Mapimpi up perfectly: ‘He just wants to play and to finish.’

Teaser video: Special awards issue

SCOUTING FOR TALENT

Finding the next Makazole Mapimpi is rugby’s next goal. These are the boys raised in mud huts, often by their grandmothers, whose parents – if they are still alive – are out in the city looking to cobble together a living and send bread home.

There is a charming EWN interview with Mapimpi’s grandmother, Nofikelepi, who said she would ‘slaughter 10 chickens for him’ when he returned from the World Cup. It was a heart-warming moment, which had the country both in stitches and joyful tears.

But there is poignancy in her statement. Before Mapimpi broke through at Border, he was playing rugby in far-flung and forgotten places such as Peelton and Debe, where the game is loved but hardly nurtured.

The winnings, if any, would come in the form of livestock – a goat, a sheep, chickens, a crate of beer – and for a long time it seemed that Mapimpi would be stuck in that whirlpool, like a lot of his brethren who never made it out.

Former Bulldogs coach Elliot Fana has a solution to unearthing this raw talent: ‘To create more Mapimpis, you need to do two things: create a professional pathway and develop players in rural areas. That means the rural kids should be playing loads of tournaments out there and that must be accompanied by proper rugby governance.

‘Rugby is not properly governed in the Eastern Cape. We do have talent but what do we do with our talent? We cannot nurture our talent due to the fact that we are lacking financial resources and we are found wanting when it comes to proper governance. Our club rugby is dying and so is our provincial union, Border. It’s high time we take people who are knowledgeable and get them to administer our rugby. That’s the only way we can see more Mapimpis.’

[ends]