This year’s World Cup is expected to be one of the most open in years and it could come down to which team best manages the workload of their players leading into the tournament, writes GREGOR PAUL.

his year’s World Cup is expected to be one of the most open in years and it could come down to which team best manages the workload of their players leading into the tournament

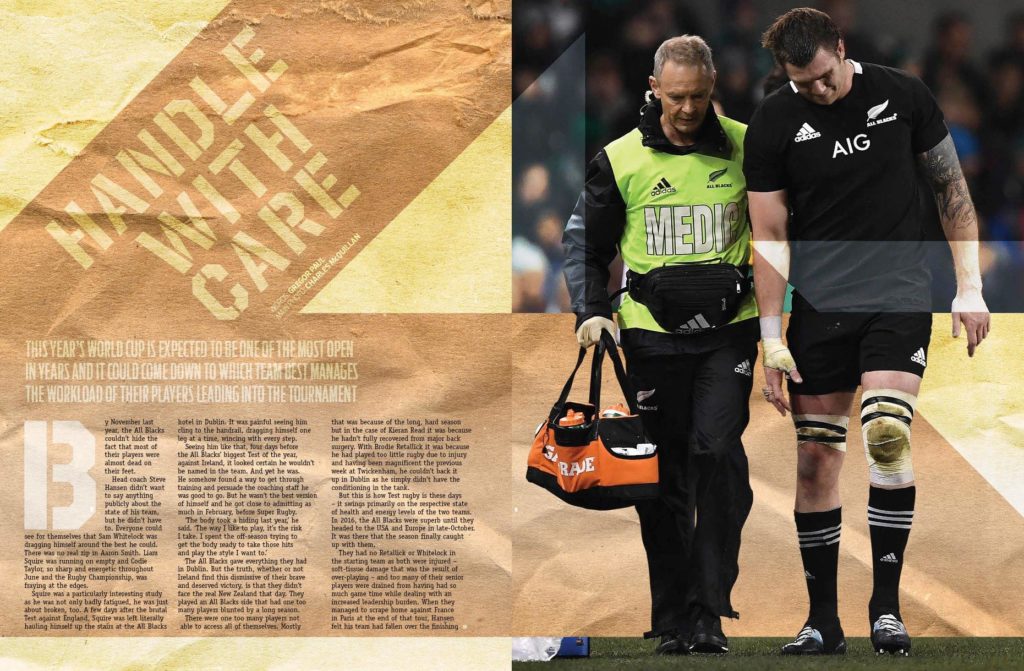

By November last year, the All Blacks couldn’t hide the fact that most of their players were about dead on their feet.

Head coach Steve Hansen didn’t want to say anything publicly about the state of his team, but he didn’t have to. Everyone could see for themselves that Sam Whitelock was dragging himself around best he could.

There was no real zip in Aaron Smith. Liam Squire was running on empty and Codie Taylor, so sharp and energetic throughout June and the Rugby Championship, was fraying at the edges.

Squire was a particularly interesting study as he was not only badly fatigued, he was just about broken, too. A few days after the brutal Test against England, Squire was left literally hauling himself up the stairs at the All Blacks hotel in Dublin. It was painful seeing him cling to the hand rail, dragging himself one leg at a time, wincing with every step.

Seeing him like that, four days prior to the All Blacks’ biggest Test of the year against Ireland, it looked certain he wouldn’t be named in the team. And yet he was. He somehow found a way to get through training and persuade the coaching staff he was good to go. But he wasn’t the best version of himself and he got close to admitting as much in February, ahead of Super Rugby.

‘The body took a hiding last year,’ he said. ‘The way I like to play, it’s the risk I take. I spent the off-season trying to get the body ready to take those hits and play the style I want to.’

The All Blacks gave everything they had in Dublin. But the truth, whether Ireland find this dismissive of their brave and deserved victory or not, is that they didn’t face the real New Zealand that day. They played an All Blacks side that had one too many players blunted by a long season. There were one too many players not able to access all of themselves.

Mostly that was because of the long hard season but in the case of Kieran Read it was because he hadn’t fully recovered from major back surgery. With Brodie Retallick it was because he had played too little rugby due to injury and having been magnificent the previous week at Twickenham, he couldn’t back it up in Dublin as he simply didn’t have the conditioning in the tank.

But this is how Test rugby is these days – it swings primarily on the respective state of health and energy levels of the two teams.

In 2016, the All Blacks were superb until they headed to the USA and Europe in late October. It was there that the season caught up with them.

They had no Retallick or Whitelock in the starting team as both were injured – soft-tissue damage that was the result of over-playing – and too many of their senior players were drained from having had so much game time, while dealing with an increased leadership burden. When they managed to scrape home against France in Paris at the end of that tour, Hansen felt his team had fallen over the finishing line and were perhaps fortunate not to have suffered more than one defeat in the last five weeks of the year.

It was that sharp decline in form at the tail end of 2016 which led to the All Blacks trying to manage things differently in 2017 – opting to not take a host of senior payers to Argentina for the Rugby Championship Test.

‘It’s always a risk but it’s also an opportunity,’ Hansen said about the plan to manage workloads during the year. ‘It’s about risk and reward. If we don’t do things differently we’re going to get to the end of the year and the three Tests in the UK will become extremely difficult because you’ve got tired athletes.’

The plan didn’t quite work as the senior players who didn’t go to Argentina struggled when they played the following week in South Africa and so the split- squad theory was shelved in 2018.

What’s become clear, or perhaps clearer, in the past three seasons is that international rugby coaches face a near impossible battle trying to play each Test with a fresh, energised and injury-free group of players. They have to juggle their resources somewhere along the way and even then it probably won’t be enough to prevent them being vulnerable in at least one if not two Tests per year.

[Smaller drop cap]

England are perhaps the side that is most exposed to the tyranny of demand. Their players answer to two separate paymasters who don’t see their interests being mutually aligned and as a consequence individuals are relentlessly flogged.

And no one can pretend that doesn’t matter. England’s form collapsed in 2018 when so many of their squad were damaged by returning from the Lions tour only to be thrust straight into action for their clubs. The injuries mounted and they were forced to dig deeper and deeper into their talent pool.

When the All Blacks played in London last November, England, despite the season being only three months old in the northern hemisphere, were already counting the casualties. Neither of the Vunipola brothers – Mako and Billy – were fit and nor was Manu Tuilagi.

Almost as damaging was the fact that those who were fit to play, didn’t have enough in their legs to be truly effective as the English club season had already taken big chunks out of some.

‘They don’t get enough of a break,’ Hansen said of all players when he arrived in London before the Test against England in November last year. ‘You can’t keep going round and round and round without running out of petrol – at some stage you’ve got to recharge the tank.

‘They’ve got one or two people injured at the moment but so does everybody, that’s the nature of the beast. That’s why I keep harping on about the need for a global season that looks after the welfare of the players. The one thing I’d really want is that everyone gets 16 weeks break between their last game and their next one.

‘The England boys have suffered a bit from the Lions tour – and it’s not only one season, it kicks on. It’s a worldwide problem and probably the team that’s managing it best at the moment is Ireland. They go “you can’t play” because they own the players and franchises completely. They’ve got a good model.’

Even Ireland, though, haven’t been able to hide their fatigue. They won an epic series against the Wallabies last June, but as the rest of the season unfolded, exposing Australia’s flaws, it became apparent that the Irish had obviously not been at their best. A fully-firing Ireland would have taken the series 3-0 instead of 2-1. To support that sentiment, Ireland had much the same personnel as they did in Australia when they faced the All Blacks in November, but they were a different team. They got off the defensive line better; they were sharper in attack, able to scramble and compete without letting up.

Having see how his own side had struggled to lift themselves at the end of a long, hard season in Australia, Ireland’s coach, Joe Schmidt, was steadfastly refusing to be carried away by his side’s 16-9 victory in November.

‘We were at home, they were on the back of a long series of games where they’ve travelled around the world a number of times, and I thought the crowd were phenomenal tonight. So, you know, that’s a lot of things stacked in our favour. So we’ll take tonight and we’ll leave the World Cup for 11 months’ time.’

This year’s Six Nations provided further evidence of how significantly injuries and fatigue can change the landscape.

England welcomed back a handful of senior players, including the Vunipola brothers and Tuilagi, and destroyed Ireland and France in consecutive weeks.

The English played with a rarely seen intensity and drive that was reminiscent of the All Blacks at their best, or more accurately, was reminiscent of the All Blacks during the Rugby Championship.

As Schmidt pointed out, the All Blacks play their last seven Tests of the year in a 10-week period that requires them to go around the world twice.

Look back to 2012 and the pattern has been the same – the All Blacks are hungry, energetic but rusty in June and then typically dynamic and accurate in the Rugby Championship, which they have won six times in the last seven years.

Usually they then start fading in the last games of the year and this would seem to be the way of things for the likes of England and Ireland as well. Their sweet spot is in the mid-part of their season just as it is for the All Blacks.

It’s at that mid-point when players tend to be at their sharpest. They have played enough football to have their instincts firing and their reactions honed but no so much that they are on dwindling energy reserves.

What all this means is that in the three years between World Cups, there is an inherent imbalance whenever northern hemisphere sides play southern hemisphere teams. One of them is always at the end of their campaign, not necessarily broken but certainly not at their peak.

World Cup years are, of course, different. They are the one occasion when every country is aiming to peak at the same time – theoretically able to manage their athletes to ensure they are still fresh and full of running in September and October. And what sort of shape the respective teams turn up in will have a major bearing on who wins the World Cup.

The difference between the best teams is infinitesimal. They are all well coached, highly skilled and capable and what will separate them in Japan is those key moments. That was the case when the All Blacks played England and Ireland last November – against the former New Zealand took their chances but didn’t against the latter.

The All Blacks didn’t look tired in Dublin but they made small mistakes that they wouldn’t usually as a result of the pressure Ireland were able to apply.

And why were Ireland able to apply effective pressure? Because they were that bit sharper, quicker, better able to cover the ground and stress the defence and close the space. It wasn’t glaring, but there were enough little victories across the game to see that Ireland were not only the better team on the day, they were in better shape.

[Smaller drop cap]

The World Cup is a different challenge entirely to a one-off Test and not just because it presents all teams with the opportunity to be there at their peak.

It’s also a brutal competition in that to win it, teams have to play seven Tests in six weeks and so it’s not just about managing players ahead of the tournament, they have to be carefully handled once they are there.

And this is where potentially the All Blacks have an advantage. They have learned the art of player management better than most of their rivals.

They have, of course, learned it painfully after their reconditioning programme of 2007 blew up in their face. The adoption of a near-paranoid strategy to keep players off the field until that year’s World Cup was a disaster and one that has never been repeated.

A more sensible approach has been taken for the last two campaigns where a handful of the most senior players have returned to Super Rugby later than everyone else while a wider group of All Blacks have been afforded a little respite during the campaign – sitting out a couple of games. The fact the All Blacks went to England in 2015 with an older squad, many of whom were well into their 30s, and there was not one hint of fatigue or of key players being past it, confirmed that a balanced approach is the right way to go.

And this is largely the way the All Blacks intend to handle 2019. The deal to which everyone has agreed is that those All Blacks who toured Europe in November couldn’t play any pre-season games, they can’t play more than five games consecutively, need to miss a minimum of two games in the campaign and when they are sitting out, they shouldn’t train with the squad or be involved in the strategical planning.

There was a graduated return-to-play policy too, which meant no one was to exceed 180 minutes of game time in the first three weeks and ideally, everyone would play no more than 40 minutes one week, nor more than 60 the next and 80 only in the third.

That didn’t quite happen for everyone but it mostly did and once Super Rugby finishes in early July, the All Blacks have Tests – Argentina (away), Australia (home and away), South Africa in Wellington and Tonga in Hamilton.

They will most likely use an expanded squad as they did in 2015, partly to give a wider group an opportunity to press their claims for inclusion, but more to spread the workload and keep everyone fresh.

The Test against Tonga has been scheduled because the All Blacks felt they went too long in 2015 between their last pre-World Cup match against Australia at Eden Park and their first pool game against Argentina. It’s easy to forget now, but the All Blacks were jittery and at times wild against the Pumas and only got the game under control when Sonny Bill Williams came off the bench and turned things around in the last half hour.

Their opening game this year is against the Springboks and they can’t afford to be rusty, hence the reason for inviting Tonga to New Zealand three weeks after they play Australia and two weeks before they take on the Boks in Yokohama.

It’s not a foolproof system by any means as inevitably there will be some who suffer serious injury and miss the tournament, but it’s a sound plan according to both current and former All Blacks.

Dan Carter, who timed his run perfectly into the 2015 tournament, certainly feels the All Blacks are again handling their players sensibly and he is confident they will be in good physical shape when they arrive in Japan.

‘It’s going to be a competitive World Cup and I like the way the All Blacks are managing players to make sure they’re peaking at the right time,’ he said. ‘They’re trying some new things and will settle on the style of play they think will win the World Cup. The coaching group are pretty smart and talented and will make sure the players don’t get ahead of themselves.’

England coach Eddie Jones would love for his players to be equally well-managed in the build-up but he won’t be afforded that luxury. Once his players finish in the Six Nations – and he already saw Maro Itoje and Mako Vunipola suffer campaign-ending injuries in the early rounds – they will be straight back into club action through to late-May. They will have a short off-season and then warm-up fixtures before heading to Japan. Maybe the real reason England haven’t done so well at the last two World Cups is that their players have arrived with too much having been taken out of them.

Ireland, who stack as another serious contender, also have a poor World Cup record. Their issue has not been fatigue or a failure to peak at the right time as the Irish Rugby Football Union has ownership of contracts and dictates when individuals can and can’t play.

What’s scuppered them has been their failure to cope with pressure. They came to France in 2007 believing they had a once-in-a-generation group of players only to lose to Argentina and France and fail to get out their pool. In 2011, they opened with a spectacular victory against the Wallabies to top their pool only to crumble in their quarter-final against Wales. And in 2015, with the whole of Ireland certain their team would make the last four for the first time, they were torn to shreds by the Pumas in Cardiff.

There was further evidence of Ireland’s mental fragility when they came into the Six Nations as favourites, only to be crushed by England at home in their opening game. The Irish, it seems, are more suited to the role of underdog and don’t enjoy being the team everyone wants to beat. This is in stark contrast to the All Blacks’ who are always the favourites – permanently expected to win no matter who they are playing and this, reckons Hansen, becomes a significant advantage at World Cups.

‘At a World Cup you have got everyone trying to win,’ said Hansen. ‘When we play, everyone is trying to beat us. They could beat us and lose for the rest of the season and still say they have had a great year because they beat the All Blacks. But when you go to the World Cup you are going to get judged on whether you win it or not. And that is every tier-one union that has genuine hopes. Ireland, England, Scotland had a good 2018 … Wales, Argentina, Australia, South Africa … these teams will go there hoping to win it.

‘Therefore their fans will also be hoping that so that will bring pressure that doesn’t normally come because you have got to win every game. You might get lucky and lose one in the pool stage but expectation creates a pressure that not many teams are used to.

‘But us … we live that every day. This will be my fifth World Cup, and we have got a good, strong management group. We have a number of players who have been to a World Cup and a number who haven’t, so that will bring some excitement. I think we are in good shape.’

*Paul is the editor of NZ Rugby World magazine and a rugby writer for the New Zealand Herald.