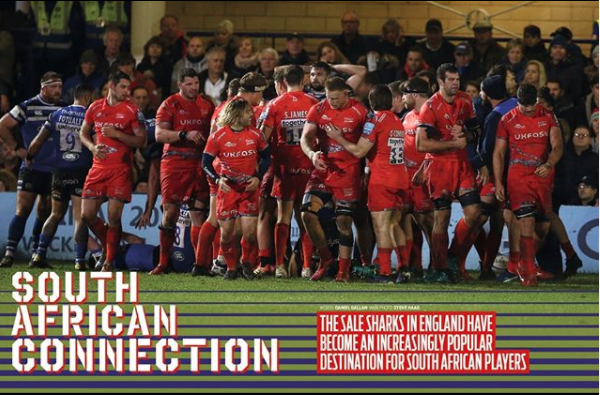

English club the Sale Sharks has become an increasingly popular destination for South African players, writes DANIEL GALLAN in the latest issue of SA Rugby magazine.

Manchester, in England’s north west, is no place for a South African. With its average rainfall of 929mm, a yearly average temperature of 10.5°C and more than three-quarters of its sunshine blanketed behind grey skies, this is a part of the world where you would expect the unmistakable tones and missing consonants of the South African accent would be in short supply.

But if you pick the right day and venture down to the AJ Bell Stadium about 6km west of the city centre, that familiar accent could be the most prominent one you hear.

You might not find it among the 12 000 fans in this quintessentially English rugby home. Instead, you’ll have to tune your ear to the middle of the field where as many as nine South Africa-born players are in the colours of Sale Sharks.

There’s Akker van der Merwe and Coenie Oosthuizen packing down in the front row having traded the black and white Sharks of Durban for their dark blue cousins in the north. Lood de Jager towers high in the lineout as twin brothers Dan and Jean-Luc du Preez offer support in the loose. Captain Jono Ross cleans up the mess at the breakdown and steers the ship, while the talismanic combination of Faf de Klerk and Rob du Preez run the show from nine and 10. Waiting at outside centre is the battering ram Rohan Janse van Rensburg, looking just as menacing as he did when he was one of the most exciting backs in Super Rugby for the Lions not too long ago.

Injury, form and the maverick tactics of head coach Steve Diamond mean that all nine rarely share a field together. This is a moot point. It is remarkable that an English club could send out a match-day 15 with a 60% South African identity. What’s more, this revolution has coincided with improved performances on the pitch.

Before coronavirus sent a shockwave around the world and put an end to all domestic rugby in England for the 2019-20 season, Sale were on an impressive run. Since the 45-7 hammering inflicted on their home patch by the Glasgow Warriors in the European Rugby Champions Cup on 18 January, the side has been imperious.

Four wins from five matches, including an impressive 22-19 victory away to table-topping Exeter Chiefs had seen the Sharks move up to second on Premiership Rugby table. But for the intervention of a global health and economic crisis, Sale Sharks would have hosted Harlequins on 15 March for the Premiership Rugby Cup final. Having pasted the clowns of south-west London 48-10 in a league match in January, most pundits predicted a first piece of silverware in 14 years to make its way to Manchester.

‘We’ve got something special brewing here,’ Diamond tells SA Rugby Magazine. ‘There’s a real positivity about the place. The South African boys bring a lot to the table. They bring heart and energy. That’s why I signed them. To help this project to turn this club into a championship-winning one.’

Sale Sharks, in a heartland of rugby league and football (Manchester United’s Old Trafford Stadium is more than six times the size of the AJ Bell and only 800m away), has struggled with mediocrity and a preoccupation with First-Division survival for many years.

A solitary league triumph in 2006 was not a harbinger of more glory. Instead it came amid golden periods from Leicester and Wasps and arrived just before Saracens became the most dominant force in the European game. It looked as though Sale’s success would be a mere blip, but a lesson – albeit a crude one – was gleaned from the club nicknamed ‘Saffacens’.

Saracens’ upturn in fortunes in the late 2000s coincided with the arrivals of Schalk Brits, Brad Barritt and Neil de Kock, with Schalk Burger to follow. The influx of Springboks left a sour taste in the mouths of critics and some have started to level similar accusations at Sale.

Diamond has been bullish in response but journalist Alex Shaw summed up the mood in England when he asked if we should we start referring to Sale as the ‘10th province of the Republic’?

‘It can feel like that at times,’ Faf de Klerk says from his home in the trendy northern quarter of Manchester. ‘It’s great to hear South African accents, especially Afrikaans accents. It makes me feel like I’m home. We’re all conscious not to speak too much Afrikaans in training so we don’t form a clique, but it’s hard not to slip into what’s comfortable.’

De Klerk was always a dynamic player off the base of the pack but he lifted the World Cup last year a better-formed player. Though some fans might have fumed at the sight of yet another box kick, it was the blond pocket rocket’s boot, as much as his fizzing passing, that provided the Springboks with go-forward ball in Japan.

‘My game has accelerated here in England,’ De Klerk says. ‘It’s the things I knew would happen, like the wet weather, that have forced me to add strings to my bow. But it’s also the distance from home, the energy at the club, living in such a cool city. These things have made me mature as a person and have made me a much harder-working professional. I owe a lot to Sale.’

In 2017, before his departure north, De Klerk had fallen out of favour at the Lions in Johannesburg and was desperate for 1st XV action. That is when Sale approached him with the chance to reinvent his game and endure a challenge he had never faced before.

This is a narrative that equally applies to Rohan Janse van Rensburg. Once a darling of Ellis Park, the young centre had the world at his feet. At 24, he had dynamite in his thighs and steamrolled hapless tacklers every weekend. But the death of his mother, a traumatic armed robbery at his home and a lengthy knee injury within three months in 2017 saw him fall into a state of depression. He needed a change of scene and Sale needed a young centre to work outside Wallabies playmaker James O’Connor.

‘It’s hard to describe how much this club has done for me,’ Van Rensburg says. ‘I started feeling sorry for myself and didn’t want to play rugby any more. Then I moved to Manchester and everything changed. My world opened up. I really feel this is the best place for me.’

Van Rensburg and De Klerk speak glowingly about the multiculturalism at Sale as an important force for on-field cohesion. It’s not just South Africans and Englishmen. The flags of Wales, Scotland, Russia, New Zealand and the US are also present. Georgians, Italians, Romanians, Tongans and a list of players from other nations have also called the AJ Bell home.

‘I challenge anyone in the world to find a more international league,’ De Klerk says. ‘But it’s not just that. It’s also the most competitive.’

But why Sale? Diversity in nations and intense competition are on offer around the Premiership. Why are so many South Africans moving to the rain and cold and grey clouds of Manchester?

‘It’s a snowball effect,’ is the best that Jono Ross can offer. ‘One guy comes and speaks glowingly of the place and he lays down a marker. Then someone else looking for a move sees that player thrive and then considers moving there himself. The Du Preez brothers come as a package of sorts and we’ve had a few guys from the Sharks in Durban come over. It’s important that the guys add value.’

Ross continued: ‘Everyone has done that. The club repays them with love and a positive energy and on it goes. We’re proving what a successful organisation we can be.’

Braais in the sleet are no fun but they do occur. De Klerk and Van Rensburg wouldn’t say who the braai master is, but both mentioned Akker van der Merwe as a keen tong-hogger. A South African delicatessen just outside town provides the biltong and wors. In this unlikely place a South African rugby revolution is on the march. Only a global pandemic could halt it for now. But normality will return. Rugby will return. When it does, nine men in blue with roots deep in the southern tip of Africa will return too.

*This article first appeared in the May issue of SA Rugby magazine, which is now on sale.