The Cheetahs and Kings face an uncertain future. JON CARDINELLI investigates the far-reaching consequences in the latest SA Rugby magazine.

READ: What’s in our latest magazine?

The Covid-19 crisis has given rise to new opportunities and deep problems. While the Bulls, Lions, Sharks and Stormers seem likely to feature in a revamped Pro16 tournament from as early as March 2021, the uncertainty around the Cheetahs and Southern Kings threatens to compromise the entire South African rugby ecosystem.

SA Rugby withdrew the Cheetahs from Super Rugby in late 2017. More recently, the Bloemfontein-based franchise was deemed surplus to Pro16 requirements. Regardless of where they wash up in 2021, the Cheetahs could be without key personnel as more and more players pursue opportunities at elite clubs in South Africa and abroad.

‘It would be terribly sad if the Cheetahs didn’t feature in a competition of international standard,’ said the 2007 World Cup winner Ruan Pienaar when he was asked about the future of rugby in the Free State. ‘This region has produced some of the best players this country has seen, so it’s a very worrying time for us here.’

The Southern Kings franchise was liquidated in September and the team – as well as its feeder union Eastern Province – was told it would not compete again in 2020. Most of the top players, including scrumhalf Cameron Wright, left Port Elizabeth.

‘Will players consider going to the Kings in the future? Perhaps … if the Eastern Cape rugby community could rid itself of the characters that have run the franchise into the ground,’ Wright said. ‘It would be hard to attract players to the union otherwise. And I have to be clear, it’s a very important part of the country in terms of South African rugby.’

Indeed, both these regions matter a great deal in a broader South African context.

Fans of neighbouring franchises may well ignore the plight of a Cheetahs side that has failed to win any major titles over a period of 25 years. They may dismiss a Kings franchise that’s lurched from one controversy to another since it was established in 2009.

And yet, to say that the Free State and the Eastern Cape have contributed nothing to the South African cause would be wide of the mark.

The value of these regions lies in their schools and junior structures, and ultimately the players who they routinely offer up to the South African system. The bigger franchises and the Springboks have reaped the benefit of these structures over the past three decades.

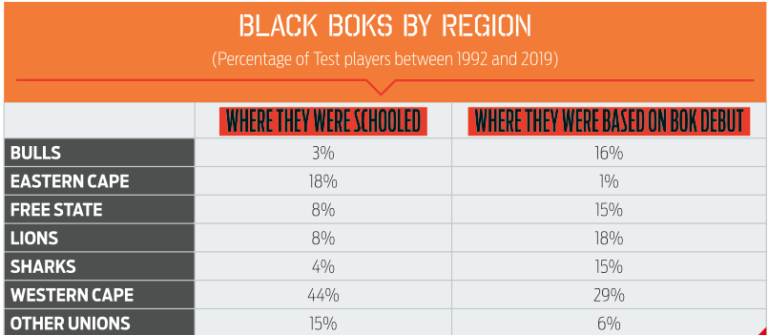

A study of the 357 players who have been capped since the Springboks’ return from isolation yields some interesting findings. The table below provides a representation of where these Boks went to high school and where they were based when they eventually received their first Test cap.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone to see that South Africa’s bigger franchises have produced the most Springboks – at least in the sense that most have earned a national call-ups while playing for the Bulls, Lions, Sharks and the Western Cape teams.

What’s interesting to note is how many of the 357 players entered the South African rugby system via teams in the Free State and Eastern Cape. More than a quarter of these players – a total of 28% – were nurtured in these schools and age-group structures before, in most cases, moving on to bigger and better things.

Bismarck du Plessis, Ruben Kruger, Cobus Reinach, Ruan Pienaar, Frans Steyn and Morne Steyn are just some of the Free State players who earned recognition while playing for ‘adopted franchises’. There are, of course, other South African legends like Juan Smith and CJ van der Linde who won national colours on the back of lengthy stints with the central franchise.

The list of top Eastern Cape players who have reached the top after joining another union – Rassie Erasmus, Siya Kolisi, Mark Andrews and Os du Randt to name a few – is far longer. Very few – 1% of all players since 1992 – have received a national call-up while based at either Eastern Province or Border. The absence of a bona fide franchise in the region has effectively encouraged these players to pursue opportunities elsewhere.

Again, one needs to consider how many players have been capped while on duty for one of the big four franchises. Players swap smaller unions for the big franchises to gain a springboard to national selection.

Gone are the days when players in the employ of Eastern Province, the Falcons or Griquas are called up to the Boks. Sad to say it, but the Free State has failed to attract the attention of national selectors in recent times. Since the Cheetahs swapped Super Rugby for the Pro14 in late 2017, only one player from the central franchise – Ox Nche – has gone on to play for the Boks.

Lukhanyo Am and Makazole Mapimpi are proud sons of the Eastern Cape, and yet Am was with the Sharks when he received a Bok call-up in 2017 and Mapimpi – who’d played for the Kings and Cheetahs previously – graduated to the national side only after spending some time with the Durban-based franchise in 2018.

Unless private investors flood the South African market and boost the smaller unions to the point where they resemble the mega-clubs in France, we’re unlikely to see a change to the status quo. The big franchises will continue to attract ambitious players, and most Test caps will continue to be won by players based at the Bulls, Lions, Sharks and Stormers.

That said, it’s important to remember where these players come from and indeed how hard SA Rugby has worked to drive transformation across the squads at provincial and national level. While the Western Cape leads in producing generic black talent, the biggest pool of ethnic black African talent is in the Eastern Cape.

The table above again highlights how many Springboks began their rugby journey in the Eastern Cape, and how many had to move to a big franchise in order to take their careers further.

In this case, the figures serve to show how nearly a fifth of South Africa’s black Springboks – 14 out of 80 – have started out in the Eastern Cape. Again, only 1% of the group has earned national selection while on duty with Border or Eastern Province.

Over the past five years, SA Rugby has made the distinction between generic black players and ethnic black African players to ensure the latter receive more opportunities. With that in mind, it’s important to note that 36% of all ethnic black Africans selected for the Boks since 1992 have been schooled in the Eastern Cape.

Kolisi, Am, Mapimpi, the Ndungane twins and Lizo Gqoboka are among those who began their rugby journey in this part of the world. Prominent players who were born in the Eastern Cape and moved to other regions before attending high school, such as Sikhumbuzo Notshe and Scarra Ntubeni, are excluded from this list – which goes to show how the list of potential stars from this area is longer than the records suggest.

It begs the question, what could the Eastern Cape build with the right backing and structures? Could they retain most of the players born, schooled and developed in the region and compete against the more-fancied franchises? With the necessary resources at their disposal, could they better identify black talent in the Eastern Cape and ensure fewer stars leave or give up on rugby altogether?

In an ideal world, the Eastern Cape would emulate its western counterpart. The Stormers have made headlines for all the wrong reasons recently, and for that they can thank the administrators as well as a system that grants the amateur arm of the organisation too much power. And yet, in spite of all that, WP and Boland continue to produce a high volume of schoolboy stars for their own teams and the other franchises.

Of the 33 players who represented the Boks at the 2019 World Cup in Japan, nine were contracted to the Stormers. A further six representing other franchises were schooled and developed in the Western Cape.

While the Cheetahs have not been as competitive as the Stormers – with only one Super Rugby playoff appearance in 2013 to speak of – they have managed to retain some, although not enough, of their homegrown talent. And until recently, players within and outside the province’s borders believed a stint at the Cheetahs might improve their chances of national selection. World Cup-winning coach Rassie Erasmus, who grew up in the Eastern Cape but received his big shot as a player at the Cheetahs, is a clear example.

Wright gets to the point about the Eastern Cape and how the Kings might excel an individual entity and as a part of a whole.

‘If SA Rugby are so passionate about the region and aware of its importance, how could they have allowed the liquidation to happen? Could they have put high-performance structures in place? Should they have left the Kings to their own devices, or should they have followed New Zealand’s lead with regard to how they manages its teams centrally?’

The last statement is key. SA Rugby has a choice. It can leave these important teams to their own devices and hope for the best, or it can move to take greater control and ensure South African rugby makes the most of its talent pool. Ultimately it can make sure South Africa harnesses the power of an entire population and achieves its transformation goals.

It’s plain to see how many Boks have come out of the Free State and Eastern Cape over the past three decades. These regions need proper franchises in elite tournaments to truly flourish, but they also need to be managed accordingly.

The Free State is a treasure and its structures should not be cast aside without a fight. The Eastern Cape remains a significant resource that is yet to be truly understood or tapped.

The numbers above suggest the talent is there. And yet, they may not represent the true depth of the player pool or the potential of the Eastern Cape and South African rugby as a whole.

It’s high time the powers that be turn their attention to that pool instead of away from it.

*This feature first appeared in the latest SA Rugby magazine, now on sale!