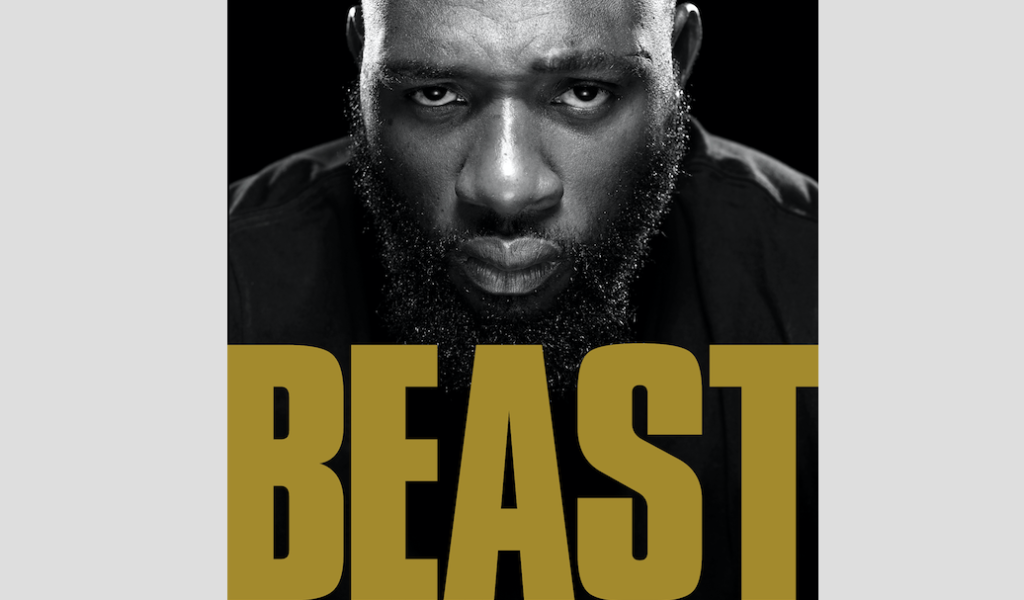

It has not been an easy journey for Beast Mtawarira, from schoolboy flank to Springbok prop, writes Mark Salter upon reviewing the World Cup-winners autobiography.

His story told in a way that reflects a warm and engaging personality, along with his general air of serenity

When Archbisop Desmond Tutu greeted the Boks at the Grand Parade, and in particular, Tendai ‘Beast’ Mtawarira, proudly sporting his World Cup gold medal, there was a metaphoric closing of the circle.

Without Bishop Tutu, there would have been no Beast as we know him

Mtawarira’s autobiography, titled simply ‘Beast’, details the difficult, nerve-wracking journey from schoolboy flank (and, believe it or not, a 100m sprinter) to one of the greatest loosehead props in the world. And never was there a more difficult time than when the officious Minister of Sport, Makhenkesi Stofile, decided in 2009 that the Zimbabwean, who had played 20 Tests for South Africa and had lived in the country for five years, was not entitled to the green and gold because he was not a full citizen. The bottom line was that Mtawarira would have to apply for full citizenship and that, he was told, could take six years.

‘I would be lying if I said it didn’t cross my mind to leave and play overseas,’ Mtawarira tells us, ‘but I never got to the stage of contacting clubs because I knew deep down my heart was here.’

Then, out of the blue came a call. ‘Is that Beast? It’s the Arch here …’

Tutu, a keen rugby fan, went on to say: ‘You are a great ambassador and role model. You represent us and this whole thing is so unfair. Don’t worry, I’m going to sort this out for you …’

Of course, it could all have been coincidence, but within a week, Mtawarira was told to report to Pretoria to pick up his citizenship papers. The Beast was back.

It is disappointing that the book does not conclude with the glorious World Cup victory in Yokohama, Beast’s finest moment in a remarkable career. It was always going to be his swansong and many believed he would spend more time on the bench than on the field, but he played six of the seven games as an integral part of the powerpack that, in a crescendo of effort, demolished the England pack so mercilessly in the final.

It evoked memories of a young Beast effectively ending the career of Phil Vickery in the first Test of the British & Irish Lions tour in 2009. I remember the indignant condemnation from sections of the British press, who claimed Mtawarira was scrumming illegally. Perhaps the best response to that was from Vickery, who said: ‘You know things haven’t gone too well when your mum, missus and sister text you to say they still love you, as they did to me that day. You live and die by your last performance and unfortunately mine was a bad day at the office.’

Of this defining moment, Mtawarira says: ‘You never set out to break someone’s spirit, but inevitably you do. From my perspective, I jut wanted to show who I was. I was saying, this is me and you didn’t respect me before, but you are going to respect me now.’

Despite the absence of the World Cup, this enlightening book is not diminished, for it an absorbing description of a journey from Churchill School in Harare to the Sharks Academy, to the Springbok camp and to World Cup winner. Under the excellent guidance of Andy Capostagno, it is told in a way that reflects a warm and engaging personality, along with his general air of serenity, even in the most trying times, founded on deep religious conviction.

That faith was sorely tested not only by Stofile, but by a terrifying diagnosis of a heart problem in 2010. Suddenly after training, his heart started beating wildly. It was discovered he had a cardiac arrhythmia, which in itself was not serious, but required surgery. He was to have three such operations, but the most serious attack of all came when he was on the end-of-year tour in 2012, when he was flown home. ‘By now I was uncertain about my future,’ he says. ‘I had to spend longer recovering from the operation and it seemed that each time I did this, things got slower and I had to work harder to feel normal again.

But, he says, when at his lowest, he had a ‘lightbulb’ moment, and with the support of his loving wife Ku, decided to change his whole mindset. ‘I realised there were people out there who were going through a lot worse than I was, and I was going to fight.’ He has not had another attack.

All through the book, Beast comes across as a man at peace with himself.

While he admits to being a bit of a bully at the age of four, due to his size, fed by a legendary appetite, he never feels the need to tell the reader how tough he is, how he never steps back, how he can beat up even the worst of characters: his results speak for him.

Indeed, one of the more surprising lines in the book, is: ‘I think I even hit someone.’

That came as a result of his Sharks coach John Plumtree going back on his word to start Beast in a promotional Super Rugby match against the Crusaders at Twickenham in order to accommodate John Smit, who was being overshadowed by Bismark du Plessis as hooker and was moved to loosehead. Beast admits he was so angry that when he came on, with half an hour to play, ‘I just let everything out. I took it out on the Crusaders. I think I even hit someone … it may have been Richie McCaw …’

It is hard to believe, too, that Mtawarira almost threw it all away. He recounts the moment in 2006 that Dick Muir, the Sharks Super Rugby coach, told him he was going to move him from flank to loosehead.

Muir told him bluntly that he would never make it to the Boks as a flank. But as prop, ‘You will play 100 games and be a Springbok great.’ At the time Beast was so upset at the thought of changing position that he ‘went to the nearest bathroom and cried my eyes out’. Once he had accepted this, he gave it ‘110%’ and is forever indebted to BJ Botha and Balie Swart, with the help of Jannie and Bismarck du Plessis, who rearranged his mindset and his physique for his new and enduring role.

And yet, when named in a College Rovers third team match to try him out in his new role, he ‘chickened out’.

‘I couldn’t do it. I slunk back to the clubhouse with my tail between my legs’.

He even told Muir that the game had ‘gone well’, but when the truth came out, the coach was livid and Beast broke down in tears.

‘It’s OK to be scared, but don’t ever lie to me again,’ said Muir, before sending him back to play more club matches.

‘I was grateful to be given a second chance,’ says Mtawarira, ‘so that weekend I finally started a game with the No 1 on my back.’

The rest, as they say, is history and this is his story.

New issue: Special awards edition

Feeding the beast

Mtawarira struggled with leaving his home and family when offered a place in the Sharks Academy, not least in making his R300 stipend supplement his almost insatiable craving for food. He tells a delightful tale of how he and Craig Burden discovered that a casino in Durban had a promotional offer of a 1kg steak, half a kg of chips and a litre of soft drink, which was free if you could down that lot in under 30 minutes. It remains one of Beast’s proudest achievements that he set a record of 12 minutes.

It was one of many records Beast was accumulate in a great and inspiring career.

*The autobiography Beast, with Andy Capostagno, is on sale at all leading book stores.