In the 17th instalment of a series on black rugby legends, JOHN GOLIATH looks back at the career of former Saru captain and flyhalf Fagmie Solomons.

The Bo-Kaap is a part of Cape Town that seems to automatically stimulate the senses.

The streets are narrow and parking scarce. So when you find a place to park and take a walk to your desired destination, you are greeted by the bright colours of the houses and the sweet aroma of a curry on a stove. You rarely walk past one of the shops without savouring the freshly baked koeksisters.

The icy northwesterly will kiss you straight on the lips in the winter months, while the Muslim prayers can be heard through the speakers of the nearby mosque throughout the day.

One of the Bo-Kaap’s famous sons, Fagmie Solomons, has been exposed to these sensory delights since birth. However, as a sportsman, he seemed to have more than just five senses. As a ridiculously talented rugby player and cricketer, he was blessed with vision, flair and extraordinary leadership qualities.

Two years ago, then Springbok coach Allister Coetzee was quizzed about who were the most naturally gifted and skilful sportsmen he has ever seen. Legendary Springbok scrumhalf Fourie du Preez’s name was the first out of Coetzee’s mouth. The second one was Solomons …

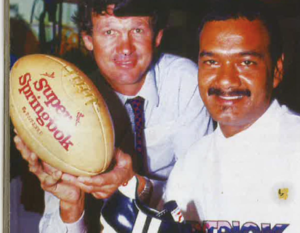

‘Former Western Province flyhalf Fagmie Solomons was a very skilful person. His passing, his kicking and his time on the ball … Those are the hallmarks of a great sportsman,’ Coetzee said.

Indeed, walking into the 61-year-old Solomons’ Bo-Kaap residence, you quickly realise this is no ordinary man. This is a legend.

To put things into perspective, in today’s era Solomons would be a combination of Handré Pollard and AB de Villiers – a great rugby player and a top cricketer.

Solomons began his senior provincial career as a 19-year-old for the non-racial Western Province Cricket Board and the Western Province Rugby Union in 1977. He began his rugby career as a quicksilver scrumhalf, before going on to be one of the best flyhalves – black or white –South Africa has ever produced.

In the summer months, Solomons was a classy middle-order batsman, who played with some of the greats of the non-racial game. It’s astonishing that he could get into that WP cricket team as a teenager in the 1970s when legends such as Lefty Adams, Rushdie and Saaid

Magiet and Braima Isaacs were in their prime.

Solomons’ bedroom wall is filled with memorabilia and pictures of his achievements, which include captaining the South African Rugby Union (Saru) team while playing outside former Eastern Province scrumhalf Coetzee. But that room wasn’t always filled with balls and cricket bats. In fact, if his mother had her way when he was a toddler, his gift to the world would not have been of the sporting kind.

‘My mother was musically inclined and my father was obsessed with rugby and cricket. This room in which we are sitting now was filled with musical instruments and the other room with sports balls. When I started to crawl, my mother always tried to steer me into this room. But she was unsuccessful,’ Solomons says with a laugh.

‘From a young age I wanted to play sport and I wanted to be the best. If I stepped on a field and a player was better than me, I wanted to prove – even just for that day – that I was the better player.’

He certainly became the best flyhalf and one of the most recognisable sportsmen in the stable of the South African Council on Sport (Sacos), whose motto of ‘no normal sport in an abnormal society’ was the driving force to end apartheid in South Africa.

In fact, Solomons was even approached by the Federation and the whites-only SA Rugby Board, which was led by Danie Craven, to cross over. But ‘Fluffy’ refused to make the switch, and in 1987 went on to lead the non-racial Saru team in their first match outside the country, in Namibia.

‘I was offered money to play for the Federation, but I declined because we believed in “no normal sport in an abnormal society”,’ Solomons says.

right in the middle row and Allister Coetzee third from the right in the front row

‘We were guided by administrators, who believed that sport must play a big role in defeating apartheid, and today I believe we should rename Athlone Stadium the Hassan Howa Stadium and the Green Point Track must be named after Noortjie Khan. They deserve that honour, because of their sacrifices.

‘Today I can say I have no regrets. The sacrifices we made were important.’

But it was the Bo-Kaap that initially shaped Solomons. His flair and skills were honed in those narrow streets, his senses stimulated by his surroundings.

‘My brother used to fill a sock with newspapers and we would use that as a ball at three, four years old. We played wherever there was space to play,’ says Solomons. ‘I think I developed a lot of skills back then, unknowingly. The foundation was perfect for me.’

– This article first appeared in the July 2018 issue of SA Rugby magazine