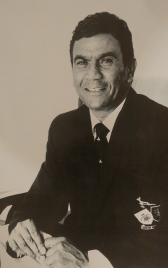

In the fifth instalment of SA Rugby magazine’s series on black rugby legends, GARY BOSHOFF looks at the career of former Proteas captain Dougie Dyers.

EARLY LIFE

Dougie Dyers, the international rugby captain, coach and administrator, turned 80 this year.

Listening to ‘oom Dougie’ talk about his fascinating life and the massive part rugby played in it, is enough to generate endless admiration for the man who played a pivotal role in many ‘firsts’ for South African rugby.

He grew up in a second-generation rugby-crazy family and continued to spread the legacy to his three sons and, more importantly, to the many rugby clubs, players and communities he encountered during his career.

The Dyers family are direct descendants of Samson Dyers, an American whale hunter who came to South Africa in 1806 as a member of the American merchant navy. He liked it here so much he decided to settle on Dyers Island, a small outcrop off the coast of Gansbaai, in the Western Cape. There he started his fishing business and collected guano, which he sold as fertilizer to the locals. Samson was the start of a long line of descendants, who would have a massive impact on rugby in this country.

Dougie’s grandfather, Paul Samuel Dyers, moved from Bredasdorp to Parow in the early 1900s and in 1903 established the Parow and Districts Rugby Union. He became the first president of the union and established Ramblers Rugby Club. Dougie’s father, also named Dougie, and four of his brothers played for Ramblers, which was referred to as the Dyers ‘family club’. Dougie grew up in an environment dominated by rugby and was destined to follow in his father and uncles’ footsteps.

‘In those days there were no sporting activities at school level; this was also the case at Norwood Central Primary School, which I attended,’ he says. However, at Vasco High he was coached by Willie Piek, whom he held in high regard and added significant value to his growth as a rugby player. But it was as a member of the Ramblers club that he came to understand the intricacies and dynamism of the game – and embraced rugby as a vehicle to forge community development and social cohesion in his home town of Parow.

RUGBY CAREER

At Ramblers Rugby Club, Dyers excelled as a loose forward and at 19 was selected for the Parow and Districts team (union) that played matches against Southerns (Overberg region), South Western Districts (SWD) and Cape Northerns (which later became Northerns).

Over the next four years he continued to play representative rugby for the Parow Union and established himself as a leader and regular 1st XV player.

In 1961, at the age of 24, he moved to Walvis Bay in Namibia (then South West Africa) as part of a construction team. Dyers couldn’t bear the fact he couldn’t play his favourite sport and established a local rugby club that would allow him to play matches.

A few years later, on his return to South Africa, he was shocked to find his Parow community in disarray as the introduction of apartheid laws by the then Nationalist government was starting to impact on schools, churches and sport clubs. Ramblers had to close due to the relocation of the local coloured community. His family moved to Bellville and he settled in Elsies River, where he joined the Blue Birds Rugby Club, which formed part of the new Northerns Rugby Union.

Dyers fondly remembers the years of the Silver Cup Trophy, which was the top club competition for the South African Rugby Federation (Sarf) unions. He excitedly recalls matches for Blue Birds against other regions’ club champions like Groot Brak River, Progress of Caledon and Osborne of Bellville. He talks about great players like Saul van der Schyff, David Habelgaarn, Daniel ‘Datie’ Petersen, Dan Hurling and Jacobus Jeposa.

In 1971, Dyers was appointed captain of the first coloured touring side to leave the shores of South Africa and the following year he captained the first coloured side to play against an international touring side, England, on South African soil. He talks with pride about the achievements of his touring side, which, under very difficult circumstances, gave a good account of themselves in England. The result he is most proud of was the 1972 match against John Pullin’s touring English side, which the Proteas lost 11-6 – the winning try came in the last minute. Two weeks later the same English team would beat the Springboks in a one-off Test at Ellis Park.

Dyers also captained the Proteas team that played against the touring 1974 British & Irish Lions.

He continued to play club rugby during the 1970s and later moved to the front row.

‘I loved rugby so much that when I got a bit bigger I moved to the front row so that I could extend my playing career by a few years,’ he says with a laugh.

LIFE AFTER RUGBY

Dyers quickly established himself as a very capable coach and took charge of the Proteas. In 1979, he was appointed coach of the SA Barbarians, the first multiracial South African rugby team to tour outside the country. The team consisted of eight players each from the Sarb (white), Sarf (coloured) and Sara (African) unions. He coached the Barbarians again the following year for a memorable fixture against the touring Lions and later, after unity, to Fiji and Samoa. He rates this tour as one of the highlights of his coaching career, as it was the first time players from the non-racial Saru had been part of a touring side representing South Africa. Current Springbok coach Allister Coetzee was a member of that squad.

In 1983, Dyers was approached by Danie Craven to take up a position at Sarb, which he accepted. ‘I had to grab the opportunity, as I firmly believed that I could make a difference to the future of coloured and black rugby players,’ he says.

His objective was to ensure the improvement and provision of facilities in underprivileged communities received urgent attention, but, more importantly, to create opportunities for coloured and black coaches to be trained and graded as coaches.

‘Talent alone will not be enough; our challenge was to improve coaching and rugby infrastructure in our communities if our players were going to be competitive at the highest level.’

Better coaching, facilities and competitions breed positive self-image and increased confidence. This recipe, he firmly believed would produce more Springboks from the underprivileged communities of South Africa.

the SA Barbarians

Dyers also served as Springbok selector in the 1980s and recalls many hard-fought battles with his fellow selectors to get players of colour picked. He relates the firm stance he had to take to get Errol Tobias selected for the Test against the English tourists of 1984.

In 1991 he moved to the Western Province Rugby Union, where he served in the development structures of the union. He continued to serve and on his retirement in 2002 was elected to the executive of the union as junior vice-president.

Recounting the 1972 match between the Proteas and Pullin’s England team, his eyes light up when he relays that poignant minute or two before kick-off – when the significance of the game dawned on him.

‘I stared at the 15 Englishmen taking up their positions across from me and the emotions of the moment swelled up inside of me. I called my players together and reminded them why they were there, on that day, in that moment – not only to play, but to compete, to win; for justice!’

Dyers is not always recognised for the immense contribution he made to the transformation of South African rugby. In spite of this injustice, he stands out as a player, captain, coach, selector and administrator who has left an indelible mark on the game he loves so much. It is undoubtedly the mark of a pioneer.

– This article first appeared in the July 2017 issue of SA Rugby magazine