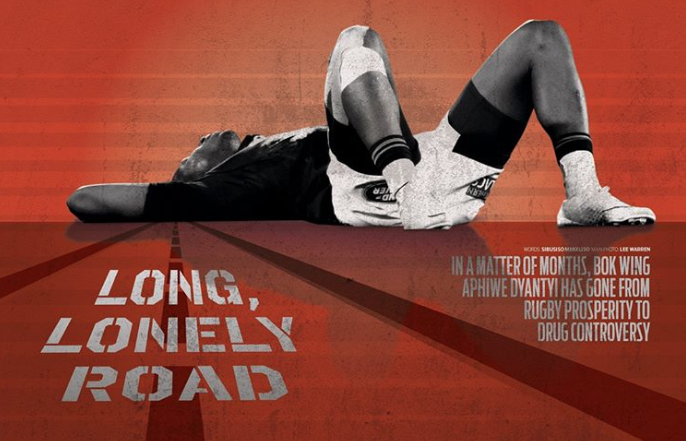

In a matter of months, Bok wing Aphiwe Dyantyi went from rugby prosperity to drug complexity. Sibusiso Mjikeliso investigates.

In what could possibly be the biggest drug-related downfall in South African sports history, Springbok Aphiwe Dyantyi is fighting to prove his innocence.

The problem is that he has, proverbially, been caught with a murder weapon, blood on his hands and a body. It is the OJ Simpson case of South African doping; complete with the race wars, conspiracy theories, media circus and conjecture.

On the morning of 24 August, the Lions and Springbok wing released a statement announcing that he’d failed a drug test. In the same statement, he revealed he’d been tested twice – once on 15 June, which he passed, and again on 2 July when he returned an adverse finding.

He stated, emphatically: ‘I want to deny ever taking any prohibited substance, intentionally or negligently to enhance my performance on the field. I believe in hard work and fair play. I have never cheated and never will.’

His mandatory ‘B’ sample came back positive six days later, four days after his 25th birthday. The SA Institute for Drug-free Sport (SAIDS) confirmed that a cocktail of banned substances including metandienone, methyltestosterone and LGD-4033 was found in his urine.

He was slapped with a provisional ban from all rugby activity, pending a tribunal hearing. He faces a four-year ban.

Social media went berserk. In the past there have been positive findings against a platoon of high-profile rugby players such as Johan Ackermann, Chiliboy Ralepelle, Johan Goosen, Ntando Kebe and Monde Hadebe, but Dyantyi’s was the highest profile of the lot.

Not only was Dyantyi a hot Springbok, who was nowhere near his peak in the game, he was also a World Rugby laureate, having won the Breakthrough Player of the Year award in 2018.

He was the Bryan Habana of his generation. He played 13 straight Test matches in his debut season, starting every game under coach Rassie Erasmus. Dyantyi was on the fast track into the Springbok World Cup squad. But an innocuous hamstring injury that ruled him out of the winter Rugby Championship squad would prove to be the end of his involvement with the national team – possibly forever.

He was a kid from rural Ngcobo in the Eastern Cape who had become a Bok in one of the hardest ways possible. Although his high school, Dale College, has an honours board full of past and present Springboks, Dyantyi had never represented its 1st XV.

He had in fact fallen out of rugby before a chance ‘koshuis’ appearance for the University of Johannesburg led to Varsity Cup stardom and eventually Springbok superstardom, all in a short space of time.

Days before news of his failed drug test broke, he sounded like he had the whole world at his feet. He spoke of how much of an inspiration he had become in his home town.

‘For the longest time, especially after that New Zealand Test in Wellington in 2018, when I got back home I had families wanting to do stuff for me, which was great,’ he said. ‘But at first I didn’t understand it. It was like, for me, “Guys, I’m still Aphiwe”. It was overwhelming. I don’t know what it feels like to be Nelson Mandela but I felt like the Nelson Mandela of my home town. It was that big.

‘I’ve learned to accept the responsibility I have to the community. I’m at a place where I inspire a lot of people, whether I like it or not. This one dude from my village came to me and said: “We are so proud of you. I never thought there would be someone from our village who would go out there and be something. We always thought that these things [being a Springbok] happened to people in other places. You have reinstalled belief in us.”’

Dyantyi’s agent, Gert van der Merwe, was quoted in reports saying they were challenging the drug finding. When contacted to shed light on their own investigation, he simply replied: ‘No comment.’

The substances paint a grim picture for Dyantyi’s chances of avoiding a guilty verdict and a four-year ban. Each drug is classified as an S1 banned substance on the World Anti-Doping Agency list, meaning they are anabolic agents that are banned in and out of competition.

Getting found with one of them is enough to get banned for up to four years, but getting found with all three was the aforementioned murder weapon, blood and body analogy. Metandienone can be found in a product called Dianabol, or ‘Dbol’ as it’s known on the streets. Those who are familiar with the performance-enhancing drug underworld call it a ‘schoolboy drug’, presumably because it is the most basic anabolic steroid and can be found in your urine 19 days after use, depending on your dosage.

Methyltestosterone is sold as a brand called Android but can commonly be found in contaminated sport supplements.

The albatross around Dyantyi’s case is the third substance, LGD-4033, better known as Ligandrol. It is a super steroid that is alleged to give the benefits of an anabolic steroid (rapid mass muscle building and fast recovery from injury) without the side-effects (such as heart disease).

‘It’s a drug that’s in the class of drugs called SARMs [Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators]. Instead of being a steroid hormone like testosterone, these drugs activate the steroid hormone receptor,’ said renowned sports scientist Dr Ross Tucker.

‘They amplify the steroid effect in the body and they improve how steroid hormones work in the body. They gain popularity pretty quickly because those in the bodybuilding world are always on the lookout for these things. They enter the market that way. Pretty soon they

make their way down to the athletes.’

Mountain to climb

Dyantyi’s challenge will be to convince a tribunal that is armed with a positive dope result, a motive (his hamstring injury) and a reasonable cause (desperation to make Erasmus’ 31-man World Cup squad).

Dyantyi was the first South African professional athlete to be caught with LGD-4033 – before women’s 100m sprinter Carina Horn also tested positive for the same substance in September.

He will have to prove that somehow these substances, two of which can be found in standalone capsules, pills or in liquid form, unwittingly got into his system and, as Dr Tucker points out, that he took every measure possible to avoid them.

‘He will have to clear a bar of convincing the panel that the drugs ended up in his body inadvertently, as opposed to intentionally, and that he took every reasonable precaution to avoid unintentional doping,’ said Dr Tucker.

‘If you’re going to show unintentional doping, you have to show where it came from. You can’t argue, “I don’t know.”

‘But if he’s going to claim it was something he ate, or something he took as a supplement, then whatever it is has to be tested and confirmed to contain the drug.

‘For Aphiwe, the challenge will be: can he show the product that gave him the positive sample? If it’s not a drug, what is it?’

Uncertain future

After the news broke, conspiracy theories started spreading like a disease, predictably on social media. Some claimed Dyantyi had been a victim of a ploy to prevent him from making the World Cup squad, while others pointed fingers at the ‘system’.

Race wars weren’t too far away either, with misplaced comparisons claiming Eben Etzebeth was treated differently to Dyantyi because of his skin colour – notwithstanding the fact the two players faced different controversies. The lock has been accused of making racist insults.

The more creative ones blamed witchcraft and there was a late submission in the conspiracy in-tray that claimed he might have taken a sexual performance-enhancer (most of which are known to contain similar ingredients as common steroids).

But the truth probably lies somewhere in between what Dyantyi knows and what science reveals. In spite of everything, he received support from the Old Dalian Union, whose president, Sinethemba Tsipa, released a carefully worded statement expressing their stance on the matter.

‘There are a lot of things that need to be found out before you can say it was intentional or not,’ Tsipa told SA Rugby magazine. ‘But regardless of the outcome, we wanted to rally support for him. When things like this happen to certain individuals, friends are few and the person might find themselves feeling alone.’

Even though he has his alma mater’s support, it could be a long, lonely road back for one of the best sport prospects this country has ever produced.

– This article first appeared in the November issue of SA Rugby magazine, now on sale